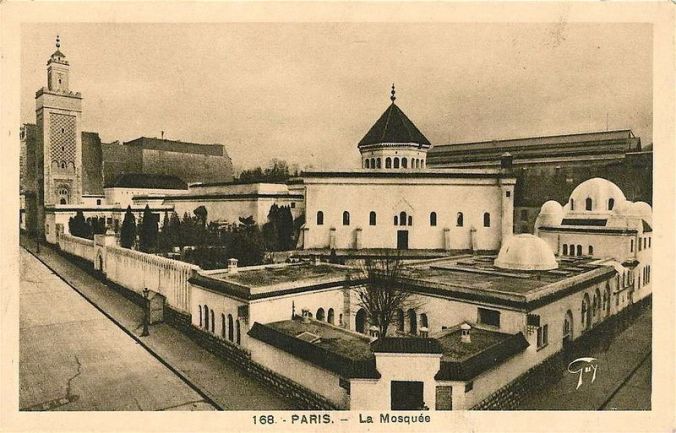

The Grand Mosque of Paris

The concept Pierre Nora presents in his article, “Between Memory and History” touches on forces adeptly rooted in politics and identity. Much of the standards he focuses on appear to be, at first glance, conflicting and almost anti-history. A hard sell, but by the second or third read (at least for myself) it becomes obvious his work is more profound and meaningful. While he provides readers the generous assumption of historical knowledge, a comparative look at his theory and a historical site considered both memorial and historical makes his work more palatable. In order to do so, we do not have to look far from his home, but to the capital of France where we find The Grand Mosque of Paris.

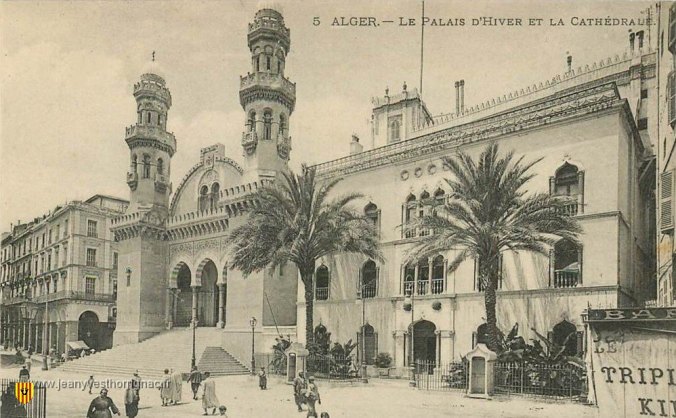

The Grand Mosque of Paris (le Grande Mosquée de Paris) is one of the oldest and largest mosques in France. Its history starts in the mid-19th century, many years before it was actually built. Like many other European countries at the time, France had a strong navy and used it for warfare and trade. The conquest of Algeria in 1830 began with the French blockade of the port in Algiers. Up until that point, Algeria had been considered Ottoman territory but enjoyed a semblance of independence so long as they did not avoid tax collectors. So when French colonialists invaded Algiers, members of the Ottoman and Algerian alliance fought back, but were ultimately unsuccessful. For over the next 100 years, Algeria was under French rule and came to be known as French Algeria.

Governor’s house in Algiers

Fast forward 80 years to World War I. The French are involved in the war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire and their allies. When the war obliged that more men be sent to the front lines, Algerian men were deployed to fight as Frenchmen against the Central Powers. Almost 30,000 Algerian men lost their life in that war, and many more still stayed in mainland France afterwards. It is this staggering statistic that instigated the then President of France Gaston Doumergue to build the Grand Mosque of Paris. In 1926, the year the mosque was opened, he dedicated the mosque to those Arab men who paid with their lives for France in World War I. It functioned to serve as a goodwill towards the Muslim (Arab) community in France, and a memorial to the many Algerian lives lost.

This is where I believe we can peel apart what Nora means when he says that, “history’s goal and ambition is not to exalt but to annihilate what has in reality taken place.” I understand my diluted description of French colonial Algeria does not begin to scratch the surface of the complexities that were involved. However, it is useful when comparing the history vs memory context within the framework of the Grand Mosque of Paris. The purpose of the mosque in the early 20th century was to commemorate the fallen men and to thank them and their family for their sacrifice. This is what the President said when it opened and is what any current tourist would hear of in terms of the mosque’s inception.

Construction of the Grand Mosque of Paris. 1924.

With this information, we can explore the subject through memory and attempt to extract the colonial past and its unspoken function for France that was decisively unsaid. The mosque failed to represent the oppressive reality that was taking place between France and Algeria at the time the mosque was constructed. Although the Algerian immigrant community had been distanced from this reality, I believe the French government understood the ramifications of a “culture clash” that was bound to catch-up within France. That is one, and I’d argue the most relevant, function of the Grand Mosque, which is specifically the French government saw a rise of distinctly un-French culture within its borders and chose to contain it within their own ability.

For me, I see Nora as an advocate for redeeming what has been lost within the selective peripheral vision of history. It was through reading his article that I remembered the difference between what sits on the surface of settings and the reality of layers beneath. I for one believe that selective history served its purpose, but has no such benefit today. The rejuvenation of lost stories through historic buildings and settings, especially those that history has left behind, is growing and will continue to grow as we let ourselves forgive our past and cradle its application to the present.